After 12 years of journaling, is it time to close the book?

Can I really let go of a habit that has served me for so long?

My first writing experiments took place in primary school. I have some vague memories sitting in the secrecy of my room, writing about my very first crush onto a neon-pink notebook, probably at the age of seven or eight, and hiding my journal very carefully, to protect it from everyone else’s eyes. That early oeuvre got lost forever, probably thrown away by my mother, who notoriously doesn’t believe in the nostalgic aura of old stuff or the need to archive it. Sadly, I can’t read those early pages, I can’t go back and study the things I chose to preserve in them. Yet I recall my desire, my wanting to write things down and keep track of them. Eventually, when I moved into puberty, I started writing and archiving consistently.

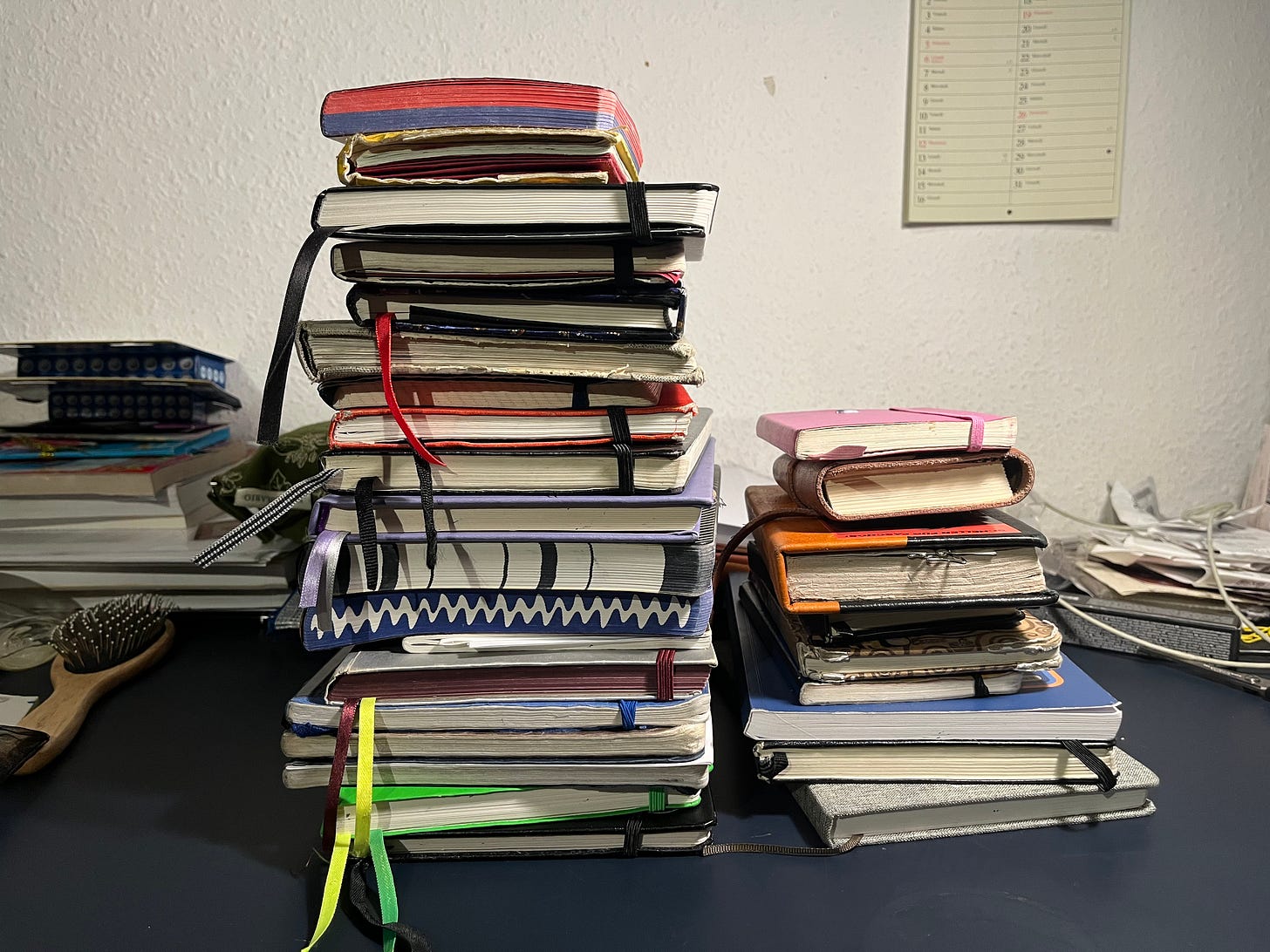

My journaling practice started between 2012-2013. I was a high school student from a small Italian town. I curated a Tumblr blog about fashion, art and photography: mostly stuff I found on other sites (remember Flickr?) and then reposted with credits. It was there that I discovered Ren Hang’s photography, Wong Kar-wai’s films, Nabokov’s Lolita and Jacques Lacan. I suspect I got the idea of journaling from Tumblr too, for some earlier pages seem to be crafted for aesthetic purposes. Maybe I was taking photos of my journals in various, aesthetic settings, and posting them onto my blog? Unfortunately, I committed digital abortion of all of my early blogging experiments many years ago, for reasons that might require a dedicated post… I digress. My point is: the blog posts are gone, but the journals remained.

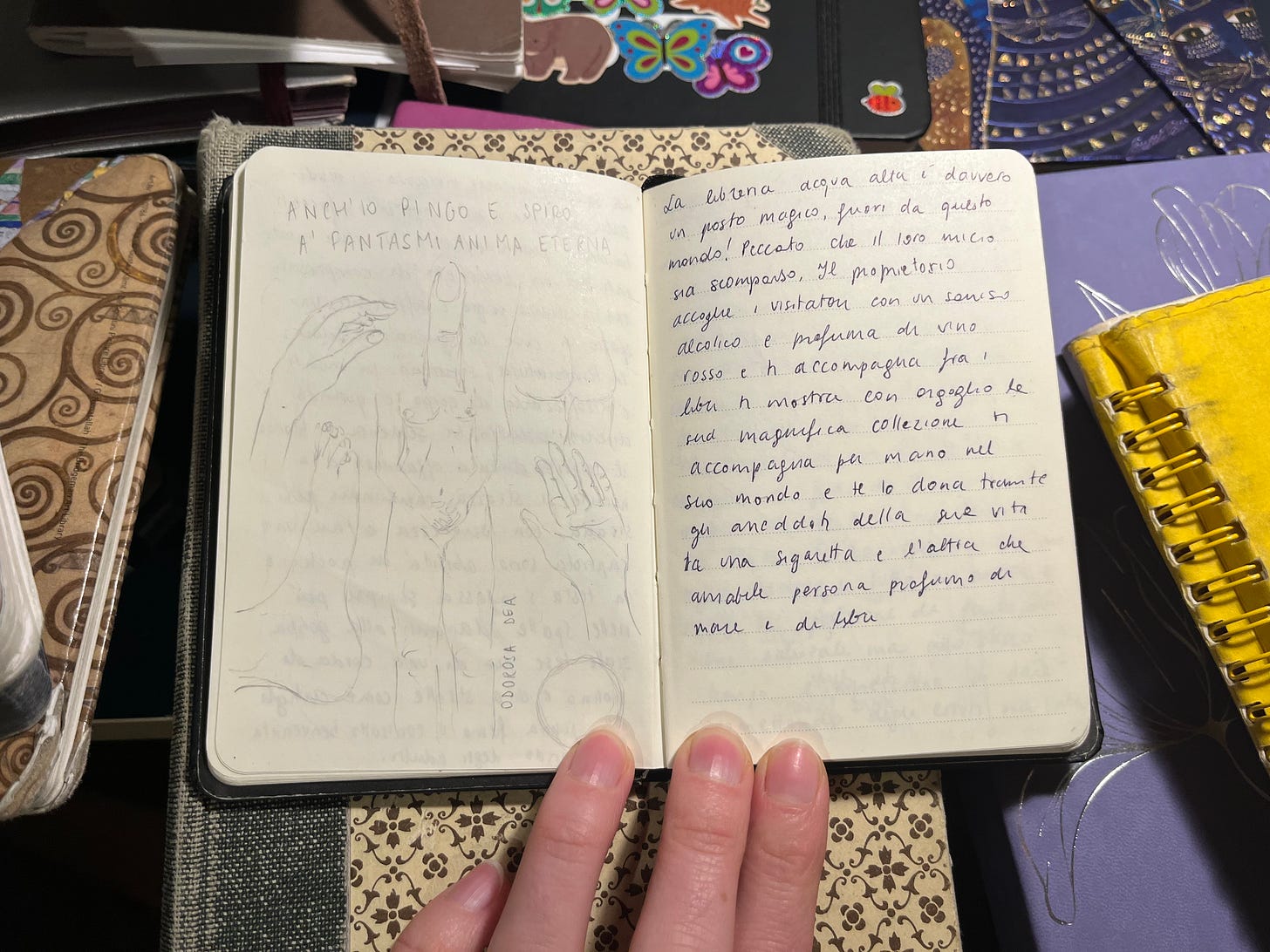

I took breaks from journaling occasionally, but mostly I wrote every single day. In the beginning, I wrote in Italian, the language I grew up with; then I wrote in English and German, the languages I mostly use in my current life. I tracked everything down: the good, the bad, the ugly. The last 12 years of my life are strictly documented. If I were interrogated about what I was doing on Wednesday, February 13th 2019, I could promptly answer that I was teaching Italian to a divorced woman who merely wanted to chat about her new dates. I went to the world exposition in Milan on a hot, humid day in the beginning of September 2015, consequently wrote a list of my new “budgeting rules,” stating: it is always allowed to spend money for trips and museums, it is always a waste to spend money on cocktails and clubs admission fees (I was 17). I used to do some drawings too and abruptly stopped circa 2017, around the time I started university. There, my writing becomes more consistent: I protocol my days, my worries, my sorrows. Sometimes it even gets experimental. I can recognize some prompts for a conscious exploration of my own interiority through journaling–probably, yet again, something found on the internet. The entries get stricter during the pandemic: it is then that I start journaling religiously, compulsively, filling three large pages from the top to the bottom, every single day, not a line more or less. Like many others in those times, I was very concerned with structure and control. I was documenting everything I ate and drank, how often I went to the toilet, how many steps I walked, how many hours I worked and how I felt: mostly miserable. Another funny pattern in my diaries is my smoking journey: I was documenting my first cigarettes in my late teens and complaining about my parents finding my first packet in my school backpack; some years later, I protocol some wild nights out with my friends from university, chain-smoking until my lungs hurt and then lighting up a cigarette first thing in the morning. Finally, for the past few years, I report wanting to quit smoking on most evenings, just to start smoking again before noon on the following day. I’ve quit the last October and since then, I occasionally journaled about how glad I am to wake up a non-smoker every single day.

To be completely honest, not all my journal-material is original. The earlier diaries are somewhat of commonplace books, where I annotated quotes from the books I read and films I watched and songs I listened to and exhibitions I visited. Yet even those less personal pages speak about me after all: when I read them, I can try to remember what I felt like in that time and what I was curious about–eventually, what I was becoming. On the other hand, through the writing I can acknowledge (or theorize) patterns: what person was I trying to be? What did I want to trace down for the future me to see? Which coherent picture of myself was I painting–a form of identity I hadn’t developed yet? The journaling allowed me to try on identities: to write the things down meant to claim them, even if just for myself. Through writing, I declared that I was an artist, a writer, a normal person, a girlfriend, a woman–but I wasn’t any of those…yet.

I still write two pages first thing in the morning every single day. My journaling practice has become completely effortless: I am so used to it that I don’t even have to think about it. I never have to make space or time for it–it is embedded in my daily routines and rhythms, just like brushing teeth or drinking coffee. But, since a couple of weeks something has shifted. I started losing interest not in the act of writing, but in the content of it. When I sit down to my journal every morning, I mostly write about quitting the journaling: what am I doing this for?

In her memoirs “Committed – on Meaning and Madwomen”, author Suzanne Scanlon writes about her rather compulsive journaling practice during her years as a “professional patient” at a long-term ward. Scanlon kept a series of notebooks, starting from the time shortly before she was institutionalized and until the present day, although the meticulous writing about “daily concerns” stopped at some point, after she left the mental hospital, after the birth of her child. Allegedly, she then started “focussing on fiction and essay and critical writing”. Scanlon returned to her notebooks in preparation for the memoirs, just to find out she couldn’t read them anymore: they were useless. Even if the notebooks could still spark memory and give clues about her own past here and there, her younger self’s writing was “crazy, insufferable, impossible”. When I read this passage of the book, I was reminded of a friend of mine, also an artist, who religiously journaled for ten years, and then just quit. He grew bored with it, he grew out of it.

It was around the same time I read Scanlon’s memoirs that I started getting these thoughts. By now, I am twenty-seven years old. I am still becoming an artist, a writer, a woman, but I’m not seventeen anymore. I have grown out of some concerns, dramas, and compulsions that fueled my journaling practice in earlier days. Likewise, I’ve grown older and I grew my tools, developing my skills as a writer, exploring new formats, new media, new spaces.

Yet, I’m still reticent to the idea of letting this practice go. If I don’t write every single morning, how will I make sense of this world? If I don’t protocol my daily experience, who will remember me and how? I sometimes fantasize about my journals being found, years and years in the future, hopefully after a prolific writing career. In my narcissistic fantasy, the journals represent a thrilling discovery that entertains and helps a hoard of scholars working on my oeuvre. At the same time, I fantasize about writing my own literary memoir: and what if going back to the diaries only brought about the disappointment Scanlon wrote about? But then again: what if I quit journaling all at once, if I stopped leaving a trace of my daily life from now on? There is a sort of archive fever, to write it in Jacques Derrida’s terms, concerning my journaling compulsion: the desperate, yet violent, drive towards fixating things in space and time, selecting which memories are kept and determining those that get destroyed. It is not merely a fixation with the future, but also the retroactive making of reality through projection. For in the end, what I (consciously or subconsciously) chose to document when I was sixteen, is still there. What I omitted, was forgotten a long time ago.